Writing about Cambodia

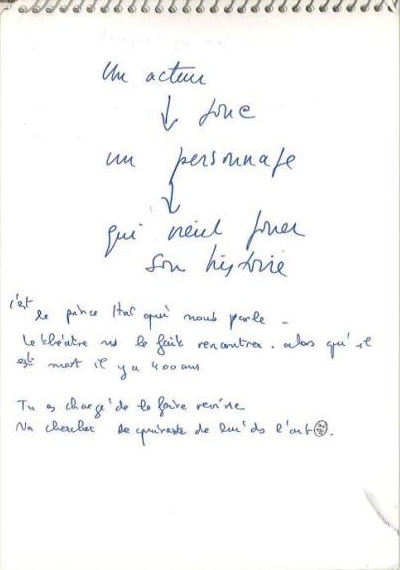

The Theater Holding Itself Responsible

When, in 1984, Ariane Mnouchkine and I try to look over the wall of time to glimpse the history to come, standing on tiptoe in the refugee and resistance camps at the Cambodian border in Thailand, nothing is completely “finished”: neither the suffering, nor the despair, nor the hope. Not long before, in 1979, Vietnam had invaded the bloodstained remains of Cambodia. King Sihanouk is clinging on for life, like the half massacred Cambodian people.

In 1985, when the vast play, The Terrible but Unfinished Story of Norodom Sihanouk, King of Cambodia, opens at the Théâtre du Soleil (in two parts of five acts each), the chaotic field of the history of a country caught in the global political cyclone, trampled, bombed from every direction by the imperialist Western and then Asian powers, destined to an auto-immune genocide, devoured by its own people, torn apart by its neighbors, is still unfolding. Such a pitiful destiny is unprecedented.

Never have makers of theater found themselves so far advanced into the ruins, in reality, at the burning turn of events, with mass graves and pockets of combatants at their sides. Never has a theatrical creation been so burdened with urgencies and responsibilities.

This play raised its characters and its scenes on the slopes of the human volcano. Theatre and History, the art and the epic poetry of events with planetary implications composed even as they are taking place, came together at the intersection of this time that is “out of joint,” as Shakespeare said, dis-jointed, dis-membered. We wanted, in the middle of the dislocation, to perform a work of remembering, of vital remembrance, re-collecting the members of a body pulled to pieces. And never had we felt such an obligation to do the necessary work of safekeeping. Without any doubt, without calculation, a pact of solidarity, a secret, even sacred alliance was established between the Théâtre du Soleil, this little community carried by the powers of the dream and an engagement in the world, and the Cambodian people, in the process of a difficult convalescence. What luck and energy came together to follow up, to assure the ethical and artistic consequences. Thus it is that a young American student, Ashley Thompson, appears as a spectator at the Theater. She “sees” The Terrible but Unfinished Story of Norodom Sihanouk, King of Cambodia. In the emotion, a remarkable decision is made within her. As if she had entered into the play as into the history of Cambodia, she goes there without delay. And within a few years, she becomes a leading scholar of Khmer civilization. Chance? Logic of emotions and thought fertilizing each other between continents.

After twenty years of work on the ground, in the name of the “Humanities,” as a specialist of Khmer culture, it occurs to her that the time has come for the new Cambodian generations to actively reappropriate, in a living and splendid form, what lies behind them in the state of a disturbing and neglected past, the silent memory of the somber red years.

When a country has terribly suffered, both from the violence exercised by the great brutal powers and from its own internecine cruelties, it vitally needs to get to know itself again through memory, narrative, reflection, harsh truth. It needs to cultivate its roots, good and bad intermingled.

The time has come and the bearers of the future are ready: at the edge of the stage are the dozens of Cambodian actors who are owed the enlightened life they are awaiting; there are also the Western, often French actors, of the Théâtre du Soleil, who go joyously to meet these Khmer generations, in order to share their double experience and make common cause – and creation – with them.

The project that is now growing, at the lovingly respectful initiative of Ashley Thompson and the Théâtre du Soleil, has a multiple aim. In the first place, to initiate young budding actors to the joys of theatrical creation, to give them the instruments and the pride of an artistic practice in which acting and knowing are combined. In the second place, to give them the mission and the possibility to rekindle the memory smouldering beneath the cinders. To take back their heritage, to become the active heroes of their destiny, to understand and re-adopt themselves. In the third place, to win back the lost time by the quickest, most exciting means: those of the imagination of the truth. To become the artists of reality, the interpreters of misfortunes and triumphs, the dancers of time. This is the goal being proposed to them, and it is not impossible to attain, because it comes with thought, friendship, desire, strength, solidarity and competence. It only lacks money.

Because art is already there: when I saw the films of the rehearsals that have been underway for several years, with scraps of cloth for a palace, a plastic chair for a throne, and a baseball cap for an army, I was moved by the strength of truth, the beauty of evocation, the extraordinary talent of these “beginners,” who are already giants. What is emerging there, in Phnom Penh or Battambang, is an unprecedented experience: the renaissance of a culture, returning to itself after a disaster, at the call of these new arrivals. Because the confidence in the cause, the conviction that the cause is just, really gives one wings.

There is currently a regiment of ragged angels in Cambodia. Their feathers are held with bits of string. They need a little money to lift them on their way.

Hélène Cixous

Théâtre du Soleil

Paris, May 2010.